TL; DR: Voice as a UI will disrupt the technology industry as we currently know it far more than people realise.

One of the most interesting questions in consumer technology at the moment is what will be the impact of voice. It is fair to say we are bullish on the future of voice, and very far from dismissive of it.

So "smart speakers", people dismiss this as being like #IoT light bulbs at their peril. Voice is the new UI for many, many things.

— Fintan Ryan (@fintanr) July 5, 2017

We are just at the start of the day to day usage of voice as a UI, but there is a dramatic shift already noticeable with the rapid growth in areas, such as Skills for the Amazon Alexa demonstrating a lot of enterprise and developer interest.

Earlier this year we attended Adobe Max, and in one of the analyst sessions a number of Adobe customers highlighted voice as being one of their biggest challenges right now. They are trying to understand how to incorporate voice into everything from their marketing campaigns to their on-going product experiences.

The Platform Companies

If we look at the current giants of the technology industry we can divide the companies, loosely, into those that are highly dependent on advertising, and those that are not.

In 2016, the last year we have full 10Ks for, Alphabet, Google’s parent company, earned 88% of their revenues from advertising, Facebook was at 97% and Twitter 89%. By contrast, none of Amazon, Microsoft or Apple have a significant dependency on advertising revenues.

Given the impact that Google and Facebook in particular have on the entire technology sector from investor sentiment to their contributions to open source technologies, we must consider their revenue sources when we look at changing consumption patterns for technology.

AdBlocking as a Signal

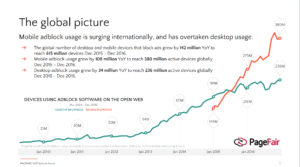

Consumers tolerance, even acceptance, of adverts in the online medium is already being tested. We have seen the rapid growth of adblocking software among more savvy consumers over the last few years, initially on the desktop, and, as noted by PageFair [1] in February of this year, increasingly on mobile.

More interestingly the barrier to making use of adblocking technology for most consumers is a lack of awareness of the options, rather than any overwhelming desire to be targeted by advertisers.

The data on AdBlocking software does not include a demographic break out, but it is a reasonably safe assumption that many of those most inclined to use such software are in the ABC1 category most coveted by advertisers. This is the same category of users who are the early adopters of technology such as Alexa, Siri and so forth.

Consumption Models

Now this leads us to a bigger question – as the UI and consumption model for many things shifts to voice, how do you place adverts, if at all? The traditional model for the web is a mix of targeted transactional adverts. The key focus is on volume with a goal of conversion for immediate sales: the promotion aspect of the 4Ps of marketing. Technology has enabled more nuanced targeting, but essentially most web advertising is focused on automating the creation of a very large funnel to convert into sales.

Consuming content from a screen is a passive interaction, in which adverts can be viewed as relatively non-invasive. Voice, however, is a very personal and active interaction. Humans enjoy conversation and interaction, but they also appreciate the terseness that voice can enable.

But most importantly, the interaction is with a voice, using your own voice – and that begins to constitute a relationship, and thus changes the marketing dynamics at play. This has the interesting side effect of shifting the advertising goals into the realm of relationship marketing. Relationship marketing has multiple definitions, but we find the definition provided by Grönroos (1994) of “establishing relationships with customers and other parties at a profit, by mutual exchange and fulfilment of promises” [2] to be particularly useful. The keywords phrases are relationship, mutual exchange and fulfilment.

The question then arises, how much of a mutual exchange is there in targeted advertising in such an active medium?

Regulatory Implications

Now we could assume that adverts will just become part of the day to day consumption of voice applications, in the same way as consumers have grown used to adverts on a screen.

But there is another factor at play in markets outside of the US. With passive consumption consumers are more or less tolerant, although you could argue they are often just plain unaware, of just how much they are being profiled by the technology companies most dependent on advertising.

But when an advert is inserted into your voice interactions, saying for example “you really should consider buying that widget, let me tell you about four options”, where the widget is something related to an item you searched for previously, on a completely different consumption – that’s a very different interaction. It is an active reminder that your browsing habits and interests are being monitored. And this leads us to privacy legislation. Or more particularly, from a European context, the GDPR.

The GDPR covers a number of areas, but of particular relevance are the consent and legitimate interest aspects of the legislation. To be profiled one must have given consent for data to be gathered in the first place, and it has to be informed consent. Consumers also have the ability both to reverse consent and to ask for their data to either be erased or no longer processed [3].

When faced with invasive advertising, will consumers begin to be more systematic in the enforcement of their rights? More importantly will consumers from other jurisdictions look at the capabilities of the GPDR and press their politicians to enact similar legislative and regulatory measures?

What Next?

This leads us to our core question – if the emergence of voice as the new UI has a significant material impact on advertising, what happens to some of today’s tech giants?

We have entered into an era where massive scale is a differentiator – and companies are happy to share the underlying work that has facilitated them operating at scale. Much of the emerging technology landscape, from cloud native to artificial intelligence, is being shaped by projects that companies, like Google and Facebook, have had a hand in either inspiring or creating. But if their revenue streams begin to be threatened will the model of openly publishing research and contributing to various projects change?

References:

- PageFair (2017), ‘The state of the blocked web’, February, [Online], Available: https://pagefair.com/downloads/2017/01/PageFair-2017-Adblock-Report.pdf [13 Dec 2017]

- Grönroos, C. (1994). ‘From marketing mix to relationship marketing: Towards a paradigm shift in marketing’. Management Decision, Vol 32(2), 4-20.

- Slaughter and May (2016), ‘Processing of personal data: consent and legitimate interests under the GDPR’, September, [Online], Available: https://www.slaughterandmay.com/media/2535723/processing-of-personal-data-consent-and-legitimate-interests-under-the-gdpr.pdf [12 Dec 2017]

Credits: Image of Kanzi, a male bonobo who can sometimes mimic human speech, Creative-Commons Attribution ShareAlike 4.0, sourced from Wikipedia.

Disclaimers: Amazon, Microsoft, Adobe and Google are current RedMonk clients. I have both a Google Home and an Amazon Echo Dot, provided for free by the respective companies.